Baking sourdough bread in the winter, even with a stiff starter, always presents problems here at my house: it’s cold! Probably not quite the cold you get in other parts of the world, but it sure is cold to me, and my starter. Kitchen temperatures are consistently hovering around 70°F (21°C) which slows fermentation activity. I’ll typically offset this by changing the percentage of mature starter carryover or by heating the water used in my feedings (a dough proofer is another great option), but I like to try to keep my starter around 76-78°F (24-25°C). Keeping my starter at that temperature is not easy to do when winter is bombarding your area! You have to make do with the warmest spot you can find in your kitchen, for me this is next to my whiskey collection. Almost poetic.

A short aside… In the winter with all the holiday events and cold weather, I find myself baking pies and cakes more and more. I recently baked an excellent lattice pie, an apple/pistachio tart, and the famous Cook’s Illustrated pecan pie, each received with equal high praise. Making a pie crust by hand becomes more accessible the more you do it (like most things), but even when it doesn’t turn out great, it’s always delicious. Butter makes life worth living, as they say. Anyway, here’s a couple of shots of two of these beauties, lots of fun to take a break from bread baking and bake something sweet.

Ok back on task here… During this challenging baking season, I’ve been experimenting with a much more stiff starter than my typical “liquid” one I’ve described thus far (outlined by Chad Robertson at Tartine Bakery). It seems many bakers argue over the differences between stiff and liquid starters, their benefits, differences, and similarities. I’ll first give a few high-level characteristics of each and then go into some things I’ve noticed after a month or more from a more personal perspective.

Frequent starter refreshments will generally lead to lower acidity, whether you’re working with a stiff or liquid starter.

Let’s first look at a very brief overview of some chemistry and biology happening inside our sourdough starters. A mature and healthy starter, and the beneficial bacteria contained within, will break down the complex carbohydrates in flour into sugars. These sugars are consumed by the yeast and bacteria, creating carbon dioxide and two types of acids as metabolic byproducts: lactic (adds a mild yogurt-like taste) and acetic (adds a more sour, vinegar taste). This symbiotic relationship between bacteria and yeast is what gives our dough leavening power in the form of CO2, and complex and layered flavors in the form of a mixture of lactic and acetic acids. You can control the production of each by the method in which you maintain your starter (frequency of feedings, water temperature, ambient temperature, etc.), the temperature it’s kept at, and the flour used when feeding. Liquid starters maintained at warmer temperature will produce more lactic acid, whereas stiff starters held at slightly cooler temperatures will make more acetic acid.

However, does this mean you’ll end up with a super sour loaf when using a stiff starter? No, not at all. Whether you’re using a stiff or liquid starter the final taste in your bread is up to you and how you decide to manage fermentation. It’s just as possible to make a sour-tasting loaf using a liquid levain (by increasing fermentation time or using a higher percentage of levain) as it is to produce a very mellow, sweet-tasting loaf using a stiff starter (which is what I prefer and always strive for).

Now let’s take a high-level look at the differences (and similarities) between a liquid and stiff starter.

Liquid Starter

Characteristics:

- hydration at, or higher than, 65% water-to-flour

- typically “sweet” or “milky” smelling if refreshed frequently as I do

- incorporating in dough mix is very easy due to its liquid nature

- refreshing is similar to stirring a thick milkshake

My liquid starter, originally started by following the guidelines set out in Tartine Bread, is a “sweet” and “milky” starter that is very loose and amorphous. I’ve maintained this high hydration starter for numerous years, and it creates bread that is very creamy tasting with a subtle sour tang to it. Many references suggest that a liquid starter will produce a final loaf that has more of a sour tang to it, but of course that all depends on how you manage other aspects of your starter (timing, temperature, etc.). More on this below.

Stiff Starter

Characteristics:

- hydration at, or less than, 65% water-to-flour

- incorporating into dough mix is a little more difficult due to the thick, tough nature

- refreshing is similar to kneading a dough

- produces a more subdued acidic taste in final loaves if maintained correctly

A stiff starter is a little more forgiving when it comes to refreshment (feeding) due to the delayed “falling” (when compared to a liquid starter which falls when food is exhausted) of the dome on top when rising. Think of it as a rising balloon in a jar that eventually runs out of helium and then suddenly the top caves in and the entire top begins to fall. There have been a few instances where I wasn’t able to attend to my starter until many hours after my regular refreshment time, and the starter was just fine — no deep vinegar smell and it was well before the total acidic breakdown of the flour.

Starter Conclusions

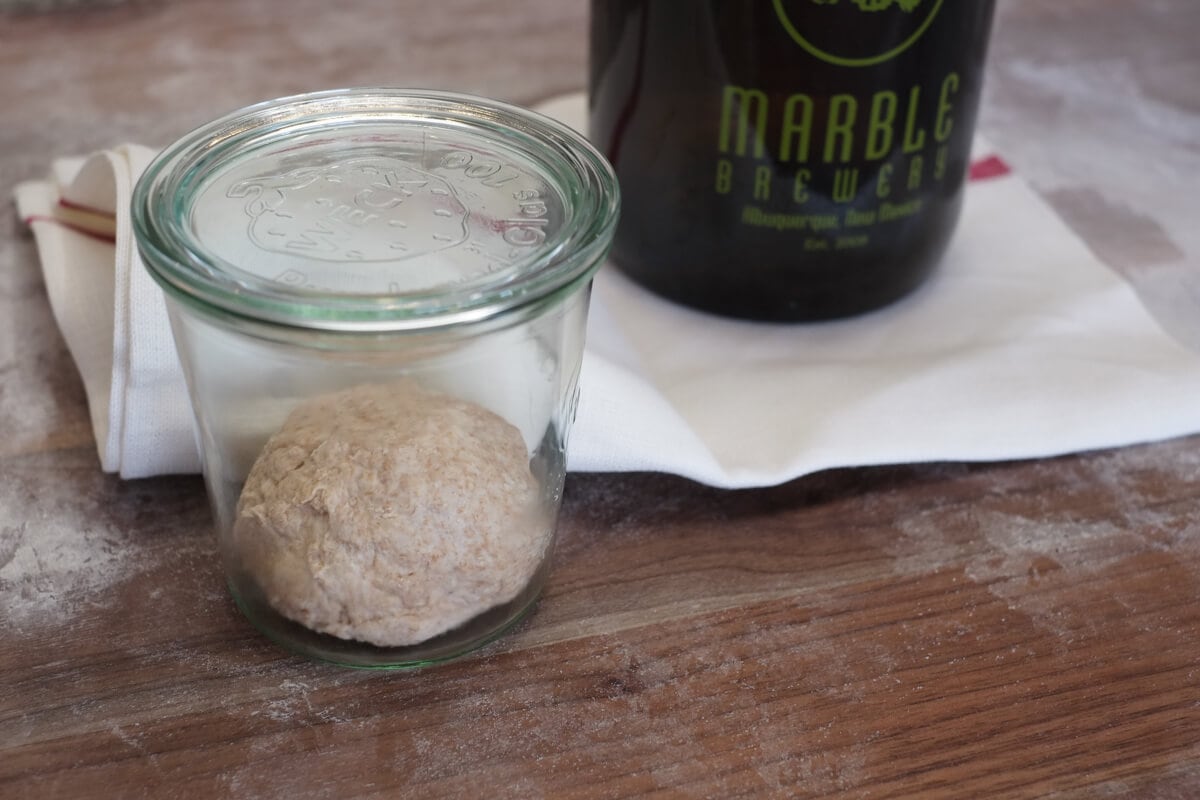

Experimenting with a stiff starter has been a very worthwhile endeavor for me, I’ve learned about the different feel, fermentation behavior and taste between using the two types of starters and levain types. Honestly, in the end, I think the choice between the two mostly comes down to your personal preference: do you like to stir your levain like a milkshake when refreshing or do you want to scoop it out and quickly knead & mix by hand? I find myself preferring the latter, surprisingly. It’s quick and easy for me to drop in some flour, water, and knead out the dough on my work surface, then drop the dry ball back into its rising jar. No messy soup to deal with. Additionally, when mixing up a high hydration recipe (like below) the stiff starter does seem to impart more strength to the final dough, giving the bread a bit more rise and making shaping a little easier. Maybe because in the end there is a little less hydration in the levain, and because of the increased acidity in the stiff starter which helps to strengthen and condition gluten.

Update:

After baking with my stiff starter for a while now, I can safely say the misconception that a stiff starter/levain produces a more sour bread is unfounded. I’ve now baked some of the most incredible tasting bread that only has a small hint of sour, probably even less than my liquid version. A stiff starter, if also fed with 100% whole wheat flour, will produce significant acidity (both lactic and acetic) but the actual transfer of these acids to your final dough is very minimal as the amount of levain used in a recipe is usually rather small

For more information, see my next post on how I maintain my sourdough starter for information on feeding (refreshment) times, flour types, and much more.

See my guide to the differences between a sourdough starter and a levain for information on how these two differ.

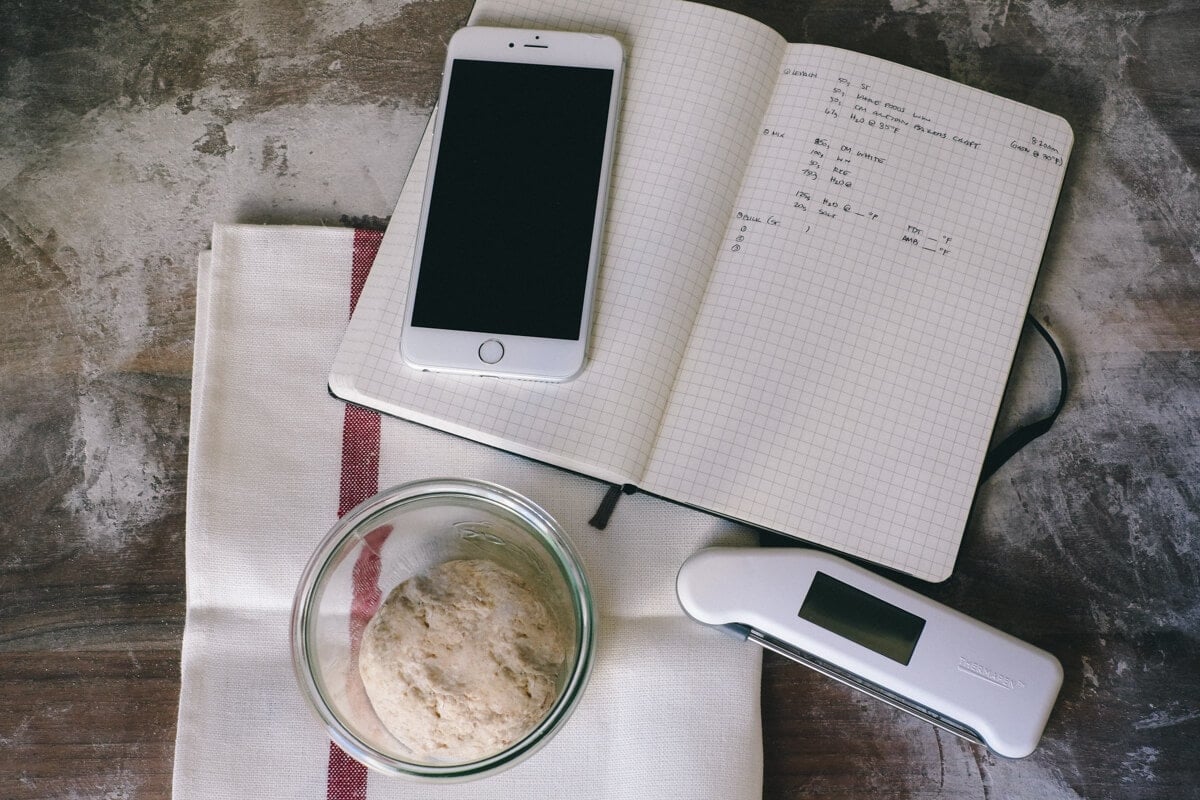

Prepare the stiff levain – 8:00 a.m.

Note that the quantities and temperatures in this entry have been adjusted to compensate for the cold environment in my house (around 70°F/21°C).

| Weight | Ingredient |

|---|---|

| 50g | Ripe starter |

| 50g | Giusto’s whole wheat flour |

| 50g | Central Milling Organic Artisan Bakers Craft (malted) |

| 65g | Water |

I keep the levain in the oven with the light on until the interior temperature reaches 78-80°F (25-26°C). Leave this to build acidity and strength for 4 or 5 hours. With a stiff levain, you’ll know it’s ready when the domed area on top begins to cave in, but after 5 hours it should be good to go.

Autolyse & Mix – 12:00 p.m.

Ingredients:

Gather the following:

| Weight | Ingredient | Baker’s Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 100g | Giusto’s whole wheat flour | 10% |

| 50g | Whole rye flour (Bob’s Red Mill Dark Rye Flour) | 5% |

| 850g | Central Milling Organic Artisan Bakers Craft (malted) | 85% |

| 875g | Water | 87.5% |

| 20g | Fine sea salt | 2% |

| 200g | Ripe, stiff levain (amount increased 5% from last entry due to cold weather) | 20% |

Perform the following for your autolyse:

- In a thick bowl add the flour

- Add 750g of your heated water (the rest is reserved until later when we add in the levain & salt after the autolyse)

- Mix these ingredients by hand until incorporated. Remember at this stage we are not looking for any gluten development, make sure all the dry bits of flour are incorporated

- Cover with wrap and keep near your levain for 1 hour (in my case in the oven to keep warm)

Slap & Fold Mix After Autolyse – 1:00 p.m.

After your one hour or so autolyse, take your dough in the bowl, break up the stiff levain on top, pour on about half the remaining water (warm water if it has cooled) and slap and fold for about 5-8 minutes until the dough looks smooth and doesn’t stick to the counter.

Return dough to the bowl and let rest for just a minute, then pour on top the salt and remaining water and do another slap and fold session for about 5 minutes until the dough again looks smooth and has some strength to it. “Strength to it” is a loaded term and this is an intuitive judgement call. After a few tries if you remain observant, you’ll start to build up a feel for “strong enough” and know when to stop your slapping & folding.

At this point, the dough should look smoother, feel elastic and strong.

| Final dough temperature: | 71°F (21°C) |

My final dough temperature was VERY cold at 71°F (21°C) (typical would be 78°F/25°C). Even with the extremely warm water having the dough exposed to air during the two slap and fold sessions cooled things off considerably. I was a bit worried at this point but performing bulk fermentation in my oven with the light on (around 80°F/26°C) let the dough proceed with fermentation, although a bit slower.

Bulk Fermentation – 1:10 p.m.

Transfer your dough to a clear container to be used during bulk fermentation and let rest for the first 30 minutes. After the first 30 minutes have passed, at 1:40 p.m., do your first set of stretch and folds. Then do two more sets, each 30 minutes after the last.

I stopped at three sets but you will need to make the call based on how your dough looks and feels. If it’s holding shape in the container, turns become a little harder to perform because the dough bundles up and it pulls easily from the sides it’s most likely strong enough and you can let rest for the remainder of the bulk fermentation.

Pre-shape – 5:10 p.m.

Take the dough out of the container onto your work surface. Divide into two halves and lightly spin the dough in little circles across your work surface with your bench knife in one hand and your other empty hand—kind of like turning a car’s steering wheel. No need to overwork the dough here! You want to gently form them into two boules, just enough to hold their shape for a 30 minddute rest, uncovered.

Shape + Proof – In Fridge at 8:40 p.m.

Shape each resting dough to your liking and place them into their flour-dusted bannetons. See my guides page for tips on shaping boules and batards. Now place these into plastic bags and let rest on the counter for 2 hours at room temperature to start proofing.

I found this rest to be necessary based on how my dough was developing and how cold it was in my kitchen—70°F (21°C)—but if it’s warmer in yours, you might want to shorten this proof period to compensate.

After this initial proof on the counter, you should have noticed your dough rise just a bit, place your bannetons with wrap into the fridge to proof overnight.

Score + Bake – around 6:00 p.m. (Next Evening)

I went for a long proof this time: about 22 hours! My theory on my fridge being too cold at 39°F (4°C) is spot-on, and you can see in the results here as there was a much more open crumb than usual due in part to the long proof. Next bake I’m going to leave the dough out even longer, perhaps 3 hours, before placing into the fridge.

Preheat your oven with a Dutch oven (or combo cooker) inside to 450°F (230°C). Once preheated, take one of your bannetons out of the fridge and cut a piece of parchment paper to place on top. Take your peel and then put it on top of those two and quickly invert it, so the dough is now resting on the parchment paper which is resting on the peel. Score the top of the dough with your desired pattern. Take out the shallow side of your Dutch oven and drag in your dough. Quickly place the pan back in the oven, cover with the deep side, and bake for 20 minutes. After 20 minutes, open the oven and take off the deep lid of the Dutch oven (set it next to the other half inside the oven), then bake for an additional 35 minutes or so, until the bread is to your desired doneness.

For more tips with baking, have a look at my guide to baking with a Dutch oven.

Conclusion

What a beautiful bake! I was happy when I sliced into these. I was pleasantly surprised by the beautiful open crumb inside, and I’m confident I can open things up a bit more next time. I’m slowly inching closer to my ideal loaf for each experiment and each trial. Sure, there are bakes that fall short, but the general progression for my bakes has been in the right direction. I’m still looking for that loaf that looks like a spider web inside with large holes and dynamic movement, almost like an explosion went off surrounded by sticky, gooey, custard.

My next attempt will be using the same procedure almost precisely as outlined above but I’ll take half and attempt a longer proof on the counter before retarding. It’s hard to say just how long will open things up more, and you don’t want to overproof, but it is an experiment after all. I’m sure it will still make excellent toast.

Crust

Thin, brittle, snaps under the lightest of pressure. Beautiful coloring throughout and excellent oven spring on these. I was a little afraid spring would suffer due to the high hydration, but the strengthening of the dough through using a stiff starter/levain and the slap and folds helped to keep things in check. Sublime coloring on the outside ranging from light brown to dark brown and signs of caramelization on the exterior. Cracks, small bubbles, tears, and rips.

Crumb

Super open, but still a little room for improvement (mostly in the bottom middle area). Tender and moist with a slightly nutty flavor likely from the whole wheat and tiny bit of rye. This bread is my current favorite sandwich bread. You can see in the image below that ghosting or shiny look to some areas where it looks like a thin sheet is being stretched wide — this is the look I want throughout.

Taste

Startling taste! My ritualistic late afternoon sandwich. With freshly baked bread shined, I couldn’t even take a minute to snap a picture to post here — it was gone. The stiff starter and managed proof did not impart an overly sour flavor to this bread; it was a mild taste that slightly lingered after finishing a bite. I like it this way, as you may know by now.

Happy New Year everyone, I hope you enjoyed this look into baking sourdough bread with a stiff starter, and I hope you join me through next year where I hope to bake and write even more—happy baking!

If you use this recipe, tag @maurizio on Instagram so I can take a look!