Baking sourdough bread at home certainly comes with challenges (or, as my enigmatic calculus professor used to tell me, opportunities for continuous growth). Baking bread at home with a consistent outcome has even more, ahem, opportunities. But one of the most critical facets for successful sourdough bread baking is learning to always monitor and adjust the dough’s temperature to get it into an optimal range for vigorous fermentation. This will help produce consistent loaves of bread with a tall rise and the most flavor.

Like a frog in a pot, sometimes we don’t even realize temperature change is happening.

I’d argue that temperature is the most important aspect of the bread-making process because it greatly impacts fermentation, which is the backbone of sourdough bread. And, of course, maintaining a consistent and sufficiently high dough temperature becomes even more difficult when ambient temperatures begin to drop (hey, winter!) or when they’re in flux (as they often are in a typical home kitchen). Like a frog in a pot, sometimes we don’t even realize temperature change is happening.

Often, we blame our sourdough starter if the dough is slow to rise or if the final loaf has lackluster flavor: it just wasn’t as lively as usual, we say, or maybe we forgot to feed it last night, we confess. While sticking to a dependable starter maintenance routine is essential, sometimes the dough’s temperature (too low or too high) is at fault. We must make simple adjustments to ensure the dough is at the right temperature for optimal fermentation activity.

Let’s first look at why temperature is so important when baking sourdough bread in the first place.

Why is Dough Temperature Important?

Temperature is the driving force in fermentation, and fermentation impacts sourdough bread volume, flavor, and texture. Warmer bread dough will ferment faster than colder dough, and strong fermentation will result in better bread. The longer the dough can ferment, the greater the opportunity the yeast and bacteria (primarily) can use to flavor the dough. But there’s a limit. If a dough ferments too long or is too warm, it can quickly overproof and degrade its structure, resulting in a poor rise in the oven.

…strong fermentation will result in better bread.

It’s also important to keep dough temperature consistent throughout the bread-making process. If we can ensure temperature consistency, we know the dough will be in the same fermentation condition throughout the lengthy process. And further, if we maintain temperatures each time we bake, we make delicious bread every time.

In other words, we cannot expect consistent results each time we bake if our dough temperature is wildly different.

There are two dough temperatures that I measure and log every time I bake: the desired dough temperature (DDT) and the final dough temperature (FDT). And yes, I keep an extensive written record of my dough temperatures to refer to them for future bakes–all to produce consistently delicious loaves!

What is the Desired Dough Temperature?

The desired dough temperature (DDT) refers to the ideal temperature for the dough at the end of mixing, just before bulk fermentation begins. Each of my recipes includes a DDT as a guide.

What is the Final Dough Temperature?

The final dough temperature (FDT) is similar to the desired dough temperature, except it’s the actual measured temperature of the dough right after mixing all the ingredients.

How Warm Should Dough Be to Rise?

The warmer a sourdough bread dough, the faster it will ferment and rise. A dough should be warm enough to encourage lively fermentation and flavor creation but not be so warm that it quickly overproofs. For most recipes here, I target a final dough temperature between 75°F to 78°F (24 to 25°C).

Bacteria and yeasts function optimally at different temperatures: 89°F (32°C) and 80°F (27°C), respectively. However, these temperatures are relatively high, so finding a happy medium at around 78°F (25°C) results in a dough that’s warm enough to have ample bacteria and yeast fermentation activity but not so warm that you end up with a dough that ferments too quickly and becomes sticky, hard to handle, and overproofs.

For doughs with a high percentage of whole grains, I typically reduce the desired dough temperature (DDT) to around 75°F (23°C) to avoid overproofing. Whole grain doughs have increased bran and germ particles in the flour, which increases fermentation activity.

| Type of dough | Approximate DDT |

|---|---|

| Mostly white flour | 75°F to 78°F (24 to 25°C) |

| Mostly whole-grain flour (including freshly milled whole grains) | 75°F (23°C) |

What Happens if My Bread Dough is Too Warm?

If you drastically overshoot the desired dough temperature, it can produce a sticky dough that quickly overproofs.

To remedy a dough that’s too warm: put the bulk fermentation container with the dough, covered, into the refrigerator for 15 to 30 minutes at the start of bulk fermentation to help bring the temperature down.

What Happens if My Bread Dough is Too Cold?

If a bread dough is cold, even if it’s just a few degrees below the desired dough temperature, it might result in a much longer bulk fermentation and/or proof time. In this case, be flexible and wait to divide or bake the dough until it displays the signs it’s ready to move on to the next step in the bread-making process.

To remedy a dough that’s too cold: put the container with dough, covered, into a warmer spot in the kitchen (or a home dough proofer; more on this below) until the temperature reaches the desired dough temperature.

Next, let’s look at measuring and monitoring dough temperature because, well, without the ability to measure, it’s hard to ensure the temperature is where we want it to be.

How to Monitor Dough Temperature

Monitoring a dough’s temperature is simple: stick an instant-read thermometer into the center of the dough and record the temperature.

I like to take the dough’s temperature at the end of mixing to record the final dough temperature in my baking notebook. I also record the dough’s temperature a few more times during bulk fermentation when I stretch and fold the dough—this is a great time to check in with the dough and see how fermentation is progressing.

Some bakers will say you don’t need a thermometer and don’t need to monitor dough temperature—strictly speaking, this is true! People have been baking bread for centuries—way before the thermometer was even invented. However, I find investing in a few simple tools, with corresponding processes, helps me take away the guesswork and make steps towards increasing my bread-making consistency. A good quality thermometer (like my Thermapen) is one such tool.

Over time, as your baking intuition builds, reliance on these tools does subside, but to this day, I always take a minute (if that) to measure the dough temperature right at the onset of bulk fermentation. Why? It provides me with an intuitive sense of how bulk fermentation will progress. Is my dough temperature a few degrees lower than I expected after mixing? If so, I’ll either warm up my dough a little at the beginning of bulk, or I’ll plan for bulk fermentation to go a little longer than planned. Conversely, if I overshot my DDT, I know bulk fermentation will likely take less time and I’ll keep an eye on the dough to divide it earlier.

Now, let’s look at how to use temperatures to ensure our dough is on target.

How to Calculate the Mixing Water Temperature for Bread Dough

Water is often the largest ingredient in a dough, so it has the largest impact on the final dough temperature (FDT). This is an opportunity for us bakers because the water’s temperature is easily adjusted, allowing us to dial in the final dough temperature easily.

If we measure the temperature of other factors—flour, the levain or preferment, the room temperature, and take into account heat generated when mixing—we can do a simple calculation to figure out to what temperature we should heat (or cool) the water to reach a recipe’s desired dough temperature (DDT).

The best way to explain all this is to run through a real-life example.

(Psst! If you don’t want to do any math, read on for a dough temperature cheat sheet.)

Example: Calculating the Mixing Water Temperature for my Beginner’s Sourdough Bread

In the following example, which is from my Beginner’s Sourdough Bread. The recipe has a DDT of 78°F (25°C). First, look at possible temperatures for each “variable” in the mixing water equation.

What are the variables—temperatures—we need?

- Levain or preferment temperature (this might be your sourdough starter, if you’re using that directly)

- Flour temperature (usually the same as your room temperature)

- Room temperature (use your Thermapen to measure this!)

- Friction factor (see below)

What is a Dough Mixer’s Friction Factor?

The friction factor temperature represents the amount the dough will heat up when mixed in a mechanical mixer. As the mixing apparatus (spiral, planetary, diving arm, etc.) spins the dough in a mixing bowl, heat is generated and must be accounted for. When mixing by hand, I typically set the friction factor to zero. The best way to determine the friction factor is to contact your mixer manufacturer or mix a test batch and measure the dough temperature difference before and after mixing.

So, back to our example, here are the temperatures I measured:

| Temperature Variable | Measured Temperature |

| Levain | 78°F (25°C) |

| Flour | 74°F (23°C) |

| Room Temperature | 74°F (23°C) |

| Friction Factor | 0 (since I’m mixing by hand) |

Mixing Water Temp = (DDT x 4) - (Levain Temp + Flour Temp + Ambient Temp + Friction Factor)

Mixing Water Temp = (78 x 4) - (78 + 74 + 74 + 0)

Required Mixing Water Temp = 86°F

We need to warm our water to 86°F (30°C) so that, at the end of our mix, our FDT will be 78°F (25°C).

Don’t Like Math?

Here’s a Calculator

I created an interactive water temperature calculator to automatically calculate what you need to warm or cool your mixing water to reach a recipe’s desired dough temperature.

OR…

Here’s a Dough Temperature Cheat Sheet

I have a cheat sheet for temperatures like this in my cookbook, but here’s a quick reference chart. The left shows what your kitchen temperature might be, and on the right, what you should warm your mixing water to so you get close to a final dough temperature of 78°F (25°C), the common goal for recipes at The Perfect Loaf.

| If your kitchen temperature is | Warm or cool the mixing water to |

| 68°F (20°C) | 98°F (37°C) |

| 70°F (21°C) | 94°F (34°C) |

| 72°F (22°C) | 90°F (32°C) |

| 74°F (23°C) | 86°F (30°C) |

| 76°F (24°C) | 82°F (28°C) |

| 78°F (25°C) | 78°F (26°C) |

| 80°F (26°C) | 74°F (23°C) |

How to Heat or Cool the Mixing Water

The easiest way to warm the mixing water temperature is to heat it in the microwave (my choice for convenience), over the stove, or draw warm water from the tap. To cool the water, use cold water from the fridge (I keep a container inside just for this) or drop a few ice cubes inside your water pitcher.

Where is The Best Place For My Dough to Rise?

Now that we know how to monitor our dough temperature and hit that all-important DDT each time, how do we ensure our dough maintains sufficient temperature through bulk fermentation and proof? As home bakers, this can be challenging because our doughs are usually smaller batches, which are more easily affected by temperature changes. Additionally, the home kitchen can also have drastic temperature changes due to heating and cooling. So, the trick is finding an optimal place for proofing dough.

These are my favorite places to let my sourdough bread dough rise:

- Inside a small home dough proofer

- Inside the home oven, closed and with the light on

- Inside the microwave

- In a warm spot in the kitchen; for me, this is on top of my refrigerator

Let’s look at each option in more detail.

Using a Home Dough Proofer to Maintain Dough Temperature

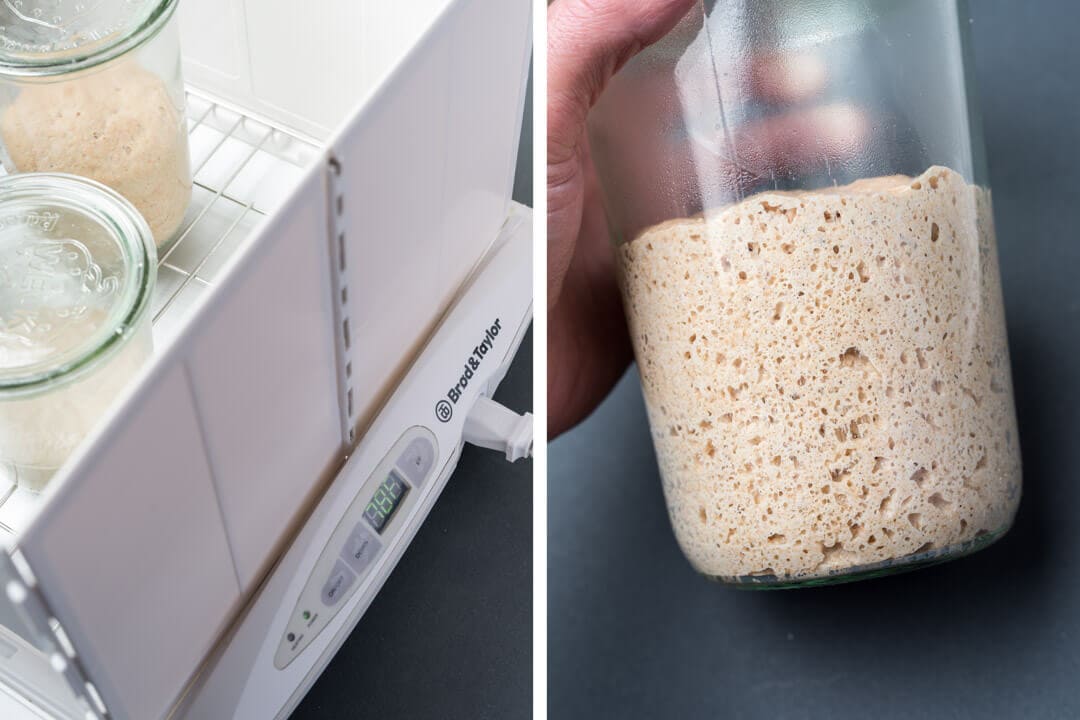

I’ve been using a Brød & Taylor dough proofer for several years. The electric proofer sits inside my pantry and runs 24/7, holding my sourdough starter (and a levain before a bake) at a comfortable 76°F (24°C) for optimal fermentation activity. Since purchasing this proofer, I have noticed a significant increase in the consistency of my bread because the temperature is so steady.

There’s enough room in the proofer to fit my starter (and even another levain) in a corner and my proofing bowl with 2kg of dough (see the picture below). This means I can have multiple bakes that are nice and warm at the same time.

What you see above is typical for a morning in my kitchen: two levain and my starter (at left) in my favorite Weck jars. The proofer is plenty spacious, and I can even fit my bulk fermentation container with these three jars.

The proofer is dead simple to use. Input the desired temperature via the up and down buttons until the desired temperature is displayed. The entire bottom of the unit is a gentle heating element designed to run continuously and maintain the set temperature. They even make a shelf you can insert midway from the bottom to hold shallow bowls or trays.

In the beginning, I mentioned that adjustments could be made in bulk if we miss our DDT by a small margin (1 to 2 degrees). If my measured FDT is a little low, I’ll turn up the heat on the proofer by 5 degrees, so the dough mass heats up at the beginning of bulk. Then, at each set of stretches and folds (30 minutes apart), I take my dough out of the proofer and take the internal temperature. If the temperature is close enough to my initial target, I’ll set the proofer back to my DDT for the remainder of bulk.

When I have dough in bulk fermentation inside the proofer, I set it exactly to the formula’s DDT. As I said before, this is typically 78°F (25°C).

Because the proofer can adjust temperature rather quickly, we can speed up and slow fermentation (within reason). There are so many handy features of a home proofer, and I recommend reading my guide to using the Brod and Taylor Proofer for an in-depth discussion.

Using a Home Oven to Maintain Dough Temperature

A home oven is another great, convenient option for maintaining dough temperature. Place your starter or bulk fermentation container in the oven (that’s turned off) with an ambient temperature thermometer inside, and turn the interior light on. Usually, this light will generate enough heat to raise the internal temperature quite a bit—just keep an eye on that thermometer to ensure it doesn’t go too high. (Additionally, put a sticky note on the outside of the oven that says “Do Not Turn On!” so someone doesn’t accidentally bake your starter.)

Using a Microwave to Maintain Dough Temperature

A microwave is a small, sealed chamber, which is rather convenient for holding a starter, levain, or bowl of rising bread dough. I typically cover my bulk fermentation container or proofing dough, and then simply place it in the microwave to help insulate the dough and keep it warm. If you want to warm up the dough, boil a small cup or bowl of water and place it inside the microwave alongside the dough.

Using a Warm Spot in Your Kitchen to Maintain Dough Temperature

Every kitchen has warm and cool spots. As bakers, we seek these out over time and learn to place our dough (and our sourdough starter) in various locations depending on its temperature needs. The top of my refrigerator is always a few degrees warmer than the rest of the kitchen. In your kitchen, the warmest spot might also be next to a coffee machine, home oven, or other secret places. Find yours!

Note: For my sourdough starter specifically, I like to keep it in my Sourdough Home, a specially designed little unit that can keep my starter and precisely the right temperature.

How does Dough Temperature Affect Bulk Fermentation Time?

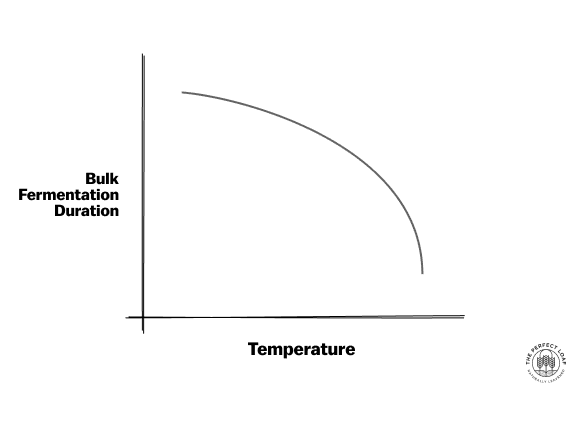

While it’s challenging (if not impossible) to assign a hard number for how long bulk fermentation should last for a particular dough, the following table shows how a range of final dough temperatures could impact this duration.

Note that this table is for illustrative purposes only and is my attempt to give a snapshot of how the bulk fermentation duration could change with varying temperatures. The table assumes all other factors are equal bake-to-bake (which is hard to ensure!) and is most accurate for the recipes and processes here at The Perfect Loaf.

| Final Dough Temperature (FDT) | Typical Bulk Fermentation Duration |

| 75°F (24°C) | 4 to 4.5 hours |

| 78°F (25°C) | 3.5 to 4 hours |

| 80°F (26°C) | 3 to 3.5 hours |

In the chart below, you can see this idea depicted roughly in a diagram: as dough temperature increases the bulk fermentation duration decreases.

Dough Temperature FAQs

When is the dough temperature for bakers calculated?

The final dough temperature (FDT) is calculated right at the end of mixing, before the start of bulk fermentation.

Where is the best place to put the dough to rise?

A warm spot in your kitchen is the best place for bread dough to rise. Try to find a place that’s between 75°F and 78°F (24°C and 25°C) to encourage strong sourdough fermentation.

What happens if the dough is too warm?

If the dough is too warm, it can become sticky, hard to handle, and eventually overproof.

Will dough rise at room temperature?

Yes, absolutely. Room temperature can mean a wide range and is different for each room, but as long as the temperature is around 68 to 76°F (20 to 24°C), you’ll get rise in your sourdough bread dough. The cooler the temperature, the longer it will take for your dough to rise.

How long can you let dough rise at room temperature?

The time you let the dough rise at warm room temperature depends on the dough formula and the exact temperature. For most sourdough bread dough, a final rise time (proof) of 1 to 4 hours at room temperature is appropriate.

What’s Next?

As bakers, I’ve talked about how we need to be acutely aware of our environment and treat temperature as importantly as our ingredients—and it is that critical: temperature is the driving force behind fermentation. To see how temperature plays a role in the final rise of sourdough bread dough, read through my guide to proofing bread dough.

Happy baking!