With this post, we welcome Eric Pallant to The Perfect Loaf as a contributor. Eric is an author, a long-time serious bread baker and sourdough enthusiast, and a professor at Allegheny College. His recent book, Sourdough Culture, is a wonderful look at the history and science of bread making through human history, and it includes a collection of delicious recipes. I’m excited to have his research narrative at the intersection of bread, science, and culture here for all to read!

Congratulations. You are a zookeeper.

If you have a sourdough starter, or had one and it died and you are trying again, or were given one by a friend and are thinking, “Now what?,” or you inherited a treasured family starter, or are a professional baker, you are responsible for the lives of billions–no, more likely decillions (that is a thousand quintillion)–of microscopic organisms you cannot see. Treat them well and they will reliably assist you in making some very delicious bread.

A good sourdough starter is an essential ingredient in the preparation of exceptional bread, but happy microbes alone will not do the trick. Also required are fresh flour, water, patience, practice, and a dynamite recipe. Fortunately, if you are reading this article, you are already aware that Maurizio Leo creates the best bread recipes on the planet. A million thanks—no, a decillion thanks—to Maurizio for inviting me to make my small additions to his outstanding oeuvre.

Maurizio has introduced me, and now I want to introduce you, to the tiny creatures you care for. I hope it improves your performance both as a zookeeper and as a baker.

Meet the Menagerie

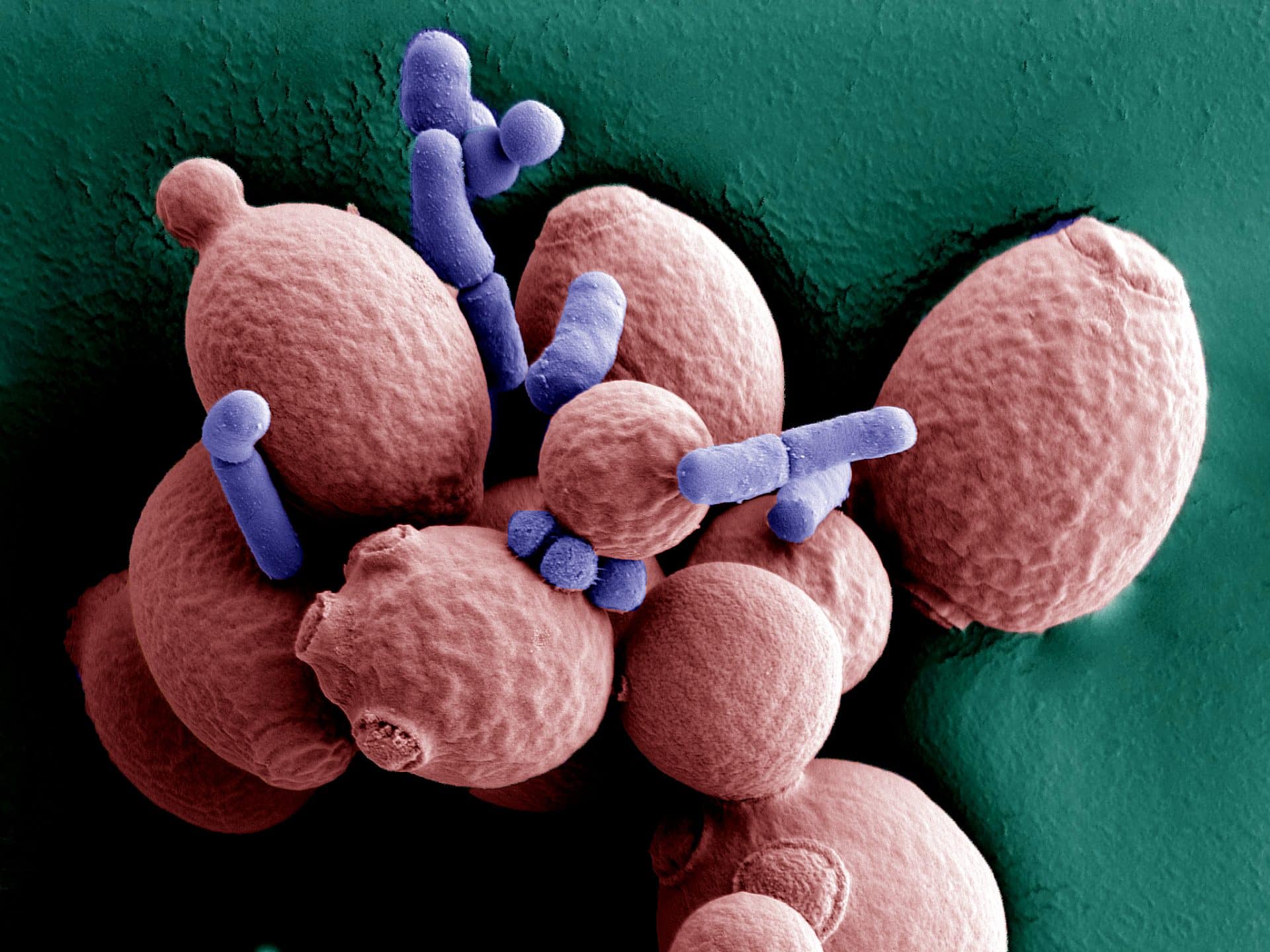

Here is a scanning electron microscope photograph of the creatures inside my sourdough culture, which came from the gold rush of 1893 in Cripple Creek, Colorado. To find out how the starter got from Colorado more than a century ago to my kitchen in Meadville, Pennsylvania—center of the universe for only about 13,000 of us—you’ll need to read my book, Sourdough Culture: A History of Bread Baking from Ancient to Modern Bakers.

Take a look at the photo and you will see large pink spheres. Those are yeast cells. They are much bigger than the purple bacterial rods. (The colors are not natural, but were added digitally by the photographer.) On the yeast cell in the upper left, you will see a new yeast cell in the process of being born. A yeast cell begins as a small bulbous protrusion, called a daughter cell, and when it is large enough to be self-sufficient, it cuts the cords that bind it to its mother, leaving behind, fittingly, a budding scar. You can see budding scars on the other yeast cells in the image.

Bacteria multiply slightly differently than yeast cells in a process called binary fission. In essence, bacteria divide themselves in half, making the commitment about who is the parent and who the offspring a Solomonic decision. This photograph is a little misleading in one way: What bacteria lack in mass, they make up with in numbers. Inside sourdough cultures, the number of bacteria cells outnumber yeast by approximately 100 to 1.

Keeping Your Starter Happy: Welcome to Your New Job

Your job as zookeeper and baker is to keep your colony of bacteria and yeast in a state of such great elation that they can think of little more than eating, excreting, and ceaseless asexual reproduction. A Roman orgy.

The billions of microscopic bacteria and yeast wiggling about inside your culture need pretty much the same things to thrive as any living organisms do. Happily you already know what those things are:

- Water

- Food

- Shelter

Exercise and love also help.

Microscopic organisms like bacteria and yeast prefer warm temperatures and, generally speaking, dark and moist environments. Keeping yeast and bacteria warm is why Maurizio promotes keeping track of the desired dough temperature (DDT). Warm microbes are happy microbes. They are also fast ones. If they get cold, your culture slows down. Put your dough or your starter into the refrigerator and it will keep working, but very slowly. Kind of like a hibernating bear. It’s still metabolizing, burning through food it has stored–fat deposits in the case of a bear, flour for your sourdough culture–but not a lot.

If conditions become really inhospitable, like way too cold, or too dry, most microbes can place themselves in suspended animation and wait for the right temperature, moisture, food, and shelter to appear. They can stay in this state of waiting for a considerable period of time, much like the seed of a plant can overwinter or stay in a purchased seed packet until it is submerged in warm, moist earth. Some bacteria and yeast can lie dormant for weeks, months, years, and even centuries. That is why if you are headed away for a very long time and cannot bake, the thing to do is to dry your starter. You’ll be able to revive it upon your return.

Putting Your Starter to Work for You

So how do you translate this biology to one of Maurizio’s recipes when it is time to bake? At the start of most bread recipes, you’ll notice that the first thing Maurizio has you do is make a levain, an off-shoot of your sourdough starter meant to be used completely in that day’s bread-making.

To make a levain, you first take a small bit of your ripe starter, place it in a new container, and then you feed and water the critters in your wildlife park. It can be helpful to first add the water, which will start waking up all those microscopic organisms. The water also gives them ample space to raise their weary heads from their neighbors’ shoulders, stretch their whatevers, and limber up. I like the term used by microbiologists for this step. They call it dispersal. Next, you better feed them soon. They will be looking for nourishment, and so right after dispersal, it is necessary to provide flour.

Honestly, there is nothing critical about the timing or order of events for making a levain (flour first, water first, add them together, whatever) so long as your new mixture gets fresh flour and water into which it can extend its colonization. Each of Maurizio’s recipes suggests the kind(s) of flour he thinks will make for the best bread, so there’s no guesswork for you. Breakfast is served!

Now, as the yeast and bacteria begin to feed, they grow. They divide. Their population increases. All on the order of minutes to hours (the process is faster at warmer temperatures). As populations expand, the bacteria excrete acids (mostly) and the yeast excrete carbon dioxide (mostly) and the culture starts to rise in its container. Now comes a tense moment, one that will repeat itself during the dough preparation process: incipient famine.

When the levain has grown–or as Maurizio calls it, ripens–you had better feed and water it again. What happens if you do not? This is how you kill a levain, a starter, or in the case of a dough, over-proof it: Starve it to death.

Instead, Maurizio’s recipes (like any decent sourdough recipe) have you take your ripe levain—critters growing, reproducing, and looking for more nourishment—and mix it with the liquids and foods (Maurizio calls them ingredients instead of foods) to make the main dough. As you mix your dough and stretch and fold it, bacteria and yeast infect (that is the microbiologist’s term for exactly what is happening) the remainder of the dough. They continue to reproduce. Your dough expands as the organisms exhale carbon dioxide. In my next installment, I will explain why and how they impart flavors to the rising dough.

At the point when they have just about run out of food again, horrible as it sounds, you need to kill them by baking them.

At the point when they have just about run out of food again, horrible as it sounds, you need to kill them by baking them. Warm temperatures are pleasant for a microbe, but temperatures higher than about 160 to 180°F (70 to 82°C) are just plain deadly. As your dough approaches its peak rise–or from the perspective of the microbes, all of the useful food has been consumed–you face a couple of options.

Option one is bake. Option two, you could begin what bakers call a retard, which is when you refrigerate the dough to slow down the organisms so that you can bake tomorrow. Or, and who among us has not had this happen, you miss the window. The dough overproofs. Like caged animals with no food or water, your microbes perish. Worse still they will poison themselves in their own waste products. An over-proofed dough will refuse to rise any further and will emerge from the oven as a hyper-sour, gummy, dense-as-a-brick doorstop.

Feeding Time

Looking back to our starter again, how often should you feed it? There is no hard and fast rule, but one experiment found that yeast and bacteria in a sourdough culture will time their growth to match their feeding schedule. Feed your starter every 24 hours and the population will reach maximum activity after 23 hours at which point they will open their microscopic little mouths and say something to the effect of, “Got any more food?”

(I have to be honest. I know I have seen a presentation with graphs of sourdough growth vs. feeding intervals. The time between feedings was on the X-axis: 24 hours; 2 days; 1 week, and so on. Microbial activity increased on the Y-axis in a gentle curve that was almost the same for every graph, meaning the microbes paced themselves to match their feeding schedule. A lightbulb turned on for me. The measured growth matched my observations over years of treating sourdough starters to different feeding intervals. Only now, despite my ceaseless Googling, I cannot find the graphs or the experimenter. I can only hope that A) I am telling the truth and B) Someone reading this will find the original study and let Maurizio and me know where it is in the comments below.)

A 24-hour feeding schedule is perfect for a professional baker. The pros do not refrigerate their starters, but simply feed them every day, except on Mondays. Monday is when she takes the day off to recover her senses from a busy weekend of production. On Tuesday, her starter will be sluggish thinking the feeding schedule has changed to every other day.

In the case of the home baker’s starter taken from the fridge once a week, or once every couple of weeks, the starter will be alive, but very, very sleepy. The longer it has been since the last feeding, the more sluggish the starter will be. A semi-dormant starter, warmed today, will barely raise bread tomorrow. Unless that is, a small population is taken and fed every 12 hours or so for a couple of days. That group of microbes will learn that its timing is twice a day and it better get going.

Tending to Your Pets

I suggest thinking of a sourdough starter as a pet–really, pets, and many of them. If you provide them with a healthy diet, keep them warm, well-loved, and regularly exercised, they will perform admirably in nearly every bake. But, if you are not a professional baker or lose track of your starter behind the orange juice and condiments, you will not lose your license as a zookeeper.

Thankfully, most starters are forgiving and maintain short memories. They can sleep for weeks, even months, between feedings, and when the urge strikes you to warm them up and start baking again, they can be coaxed back into fine form. But you will need to treat them well for the living creatures that they are and nurture them back to health.

For more on how to best feed your sourdough starter and keep it happy, check out Maurizio’s guide →