In this third post by Eric Pallant, author of Sourdough Culture: A History of Bread Making from Ancient to Modern Bakers and professor at Allegheny College, recalls his recent trip to Morocco to take a breadmaking class and in search of traditional Moroccan breads.

While this post was in the final stages of writing, the deadliest earthquake in 100 years struck Morocco. Please consider donating to earthquake relief for Moroccan communities through the High Atlas Foundation (the author has traveled and worked with the HAF in support of Morocco).

There are two things to know right off the bat about the breads of Morocco: First, they are important. Bread is served at every meal. Second, they are good. Finding the best breads is an adventure I would recommend to anyone who cares about authenticity, culture, history, and flavor.

In May and June of 2023, I had the privilege of traveling in Morocco for two weeks. I visited more than half a dozen communal bread ovens, took a bread making class where I learned to make five kinds of Moroccan bread, observed Amazigh (Berber) women making flat breads, and devoured French pastries. It was delicious.

In Morocco, bread is more than just food. In 2018, Dr. Katharina Graf, a Postdoctoral Researcher at Goethe University in Frankfurt, published Cereal Citizens: Crafting Bread and Belonging in Urbanizing Morocco. In her article, Dr. Graf writes, “Moroccans eat bread with nearly every meal. Bread simply has to be there: it is the tool to pick up food, the conveyor of a dish’s taste, the guarantor of physical satiation and the basis of caring and hospitality.”

“Manage with bread and butter until God sends honey.”

Ancient Moroccan Proverb

Yet as important as bread is to Moroccan life, it has changed significantly through the generations, becoming, well, more industrialized: you see more white flour, more commercial yeast, more store-bought from the supermarket. Rapidly disappearing are the breads made at home using locally milled whole wheat and sourdough starters. The industrialization of Moroccan bread, which is occurring while bread is maintaining its central role in Moroccan cuisine, reflects the country’s geographic and political place in the modern world.

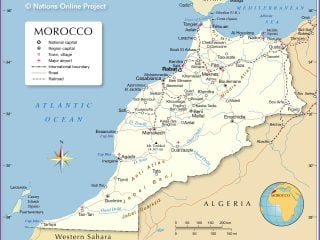

Morocco’s Geography

Let’s begin with Morocco’s geography. Just south of Spain, on the northwestern edge of the African continent, the country is partly in and partly out of the Sahara Desert. The Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts are relatively flat with fine areas for growing soft wheat. At higher elevations, in the Atlas Mountains, farmers raise Durum wheat to mill into flour that is used to make couscous as well as bread.

Wheat has been found in a Moroccan archaeological site dating from more than 7,000 years ago. Half a dozen millennia is plenty of time to experiment with turning wheat into bread–and there are a lot of different variations on bread in Morocco.

Shifting from Sourdough to Commercial Yeast

It will come as no surprise to sourdough aficionados–or (guilty plug) readers of Sourdough Culture: A History of Breadmaking from Ancient to Modern Bakers–that until the early 20th century most Moroccan breads were leavened with sourdough starters. In 1938, Somadir started preparing fresh yeast in Morocco, and today, it is the largest yeast-making company in Africa. Professional bakers and home bakers in Morocco are tempted to make the switch from sourdough to commercial yeast for the same reasons they are the world over: ease, efficiency, speed, price, and availability.

Sourdough is still used in spots around the country, especially by older folks living in rural communities. I asked a few bakers how Moroccan sourdough starters were inoculated. No small feat when trying to describe an outdated leavening agent in English to be translated into French, then Arabic, and finally to the Amazigh language of Tamazigh (and then back again). I learned that sourdough cultures launched with wheat flour also contained some fascinating add-ins: dates, whey expressed from a thick yogurt called leben, tomatoes, and chickpeas. A study published this year of 100 starters in eastern Morocco found that the following ingredients were added to sourdough starters too: lemon, garlic, dried figs, flax seeds, raisins, and carob powder.

Still, all the bread I consumed in Morocco was yeasted. I don’t think I got far enough into rural areas to find sourdough breads, though I’m sure they are out there.

Communal Ovens

Meet the traditional oven. In villages, towns, and even in large cities – Rabat (the capital), Marrakech, Casablanca, and Fez – Morocco’s communal ovens are hidden in alleyways, behind unremarkable doorways, and down a few steps into a room below street level. The bakers are all men. They fire up their ovens after the Muzzein’s pre-dawn call for morning prayer and bake until late morning.

In neighborhood households, women make dough. They lay pre-shaped dough on rectangular wooden trays lined with cloth, fold the cloth over their doughs, and every day (depending upon the household) someone makes a trip to the baker: mom, husband, son, daughter, grandmother.

Moroccan lore has it that if you want to know anything about your neighbors… the baker is the person who knows everything about everybody.

The bakers I visited told me they might have one hundred doughs cooking at one time, which begs the question of how they keep straight whose loaf belongs to whom. To outsiders, the return of a cooked loaf to its rightful owner is one of the great mysteries of Moroccan bread. But these bakers make thousands of loaves a week, and if you pause to think about it, every breadmaker has a signature. With all of that experience, the men working the ovens recognize that Mrs. Alaoui’s loaves are distinct from Mrs. Idrissi’s.

Moroccan lore has it that if you want to know anything about your neighbors–like, for instance, whether the man your daughter has her eye on would be a good husband–the baker is the person who knows everything about everybody.

Khubz: Morocco’s Daily Bread

In Arabic, the word for bread is khubz. A communal oven is known as a khubz furan. One of the most common breads in Morocco is simply called khubz. Like a pita, it is round and can be hollowed out and filled with grilled meats. In addition to baking doughs brought to them from homes, bakers churn out their own khubz by the hundreds to deliver to pocket-sized stores, restaurants, neighborhood grocers, hotels, and small riads (guest houses built around interior courtyards).

In the video below, just watch how many loaves per tray and how many trays were being filled. As loaves come out of the oven they are loaded in carts, in laundry baskets, and on the backs of motorbikes for delivery. You can find one of these vendors in the morning by walking “upstream” against the flow of people walking home with fogged plastic bags bearing a couple of warm khubz for breakfast.

Khubz are on sale everywhere all the time. At the end of the day Moroccans place leftover bread outside. I heard various explanations of this practice. They might be drying it to make bread crumbs, but more likely, days-end bread is gathered by Morocco’s poorest citizens. Some may sell it in rural areas as animal feed to generate a little income, while others are likely eating it. As Dr. Graf says, bread, in Morocco, is the basis for caring and hospitality.

Other Breads of Morocco

While round pita-like khubz are ubiquitous, there are several other notable breads that you can find throughout the country.

M’lawi (or M’Semen)

A layered, leavened flatbread, m’lawi (or m’semen) is served at breakfast with jam, as street food, or, if eaten later in the day, layered with savory meats and vegetables. It is made with a combination of white flour, fine semolina, coarse semolina, and instant yeast (though, in my opinion, it would be so much better made with a sourdough starter).

Vigorous kneading leads to strong gluten development, and then the dough is spread and stretched into a wide and very thin circle (thin enough that bakers are careful not to pull holes in the dough), doused with olive oil, sprinkled with coarse semolina, and folded upon itself. In between those folds is where you can load in fillings like ground meat, sauteed onions and spices, sliced olives, or preserved lemons.

The process of oiling, sprinkling, and folding is repeated, giving the final dough a square shape with a thickness of a little less than one-half to a little more than three-fourths of an inch.

The pancake is fried in a dry pan; there’s enough olive oil in and on the dough that the pan doesn’t need additional. The coarse semolina gives the finished bread some chew, and who doesn’t like the combination of fried dough, olive oil, and crunch?

Sh’air

Another bread commonly found in Morocco is sh’air, which is leavened and made of cracked barley that has been allowed to soak before frying. The long period for soaking in a warm climate is probably ideal for a sourdough starter, and I suspect at one time sh’air tasted sour, but the one recipe I was shown was allowed to ferment for several hours following the addition of a small amount of yeast.

Sh’air is cooked like a pancake on a hot pan, but as it is made of slightly fermented barley, rather than wheat, the final product is flavorful but very dense. Eating one would keep you full for hours.

Harsha

Similar to sh’air is another slow-cooked, thick, pancake-like bread called harsha. Harsha is made of coarse semolina flour with some olive oil. Unlike sh’air, the version I was shown had no leavening. But similar to sh’air, this bread is a substantial meal all by itself thanks to the coarse grains of semolina, absence of any leavening or gluten development, and the addition of olive oil.

Tafarnoute

Tafarnoute is a flatbread cooked on small river stones heated in an open fire. A baker blows bellows on fuelwood burning below the stones to raise the temperature of the fire. The hot stones give the bread a lumpy appearance and a flavor that carries directly from the hearth to your mouth.

Tafarnoute is Berber in origin, and though I had the great joy of watching it being baked by Amazigh women in the High Atlas Mountains and eating some until I could eat no more, I did not have a chance to see it being prepared. I suspect it is whole wheat flour, water, and salt and not much else. I have made sourdough versions at home atop stones I have heated in a pie tin in my oven. The results were delicious, and cooking on stones is great fun.

Political History and French Colonization

In 1677, the Alaouite Dynasty gained control over Morocco and ruled the country from that date until 1912, when they lost control to the imperial ambitions of Spain and France for parts of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. A series of agreements involving the European powers of the day—France, Great Britain, Italy, Portugal, and Spain—led to the not-always peaceful colonization of much of North Africa and the Middle East. France officially controlled Morocco as a protectorate from 1912 to 1956.

One way the Alaouite Monarchy maintained political stability in Morocco across centuries was by ensuring plentiful and affordable supplies of wheat for breadmaking. This is not a trivial feat in a country that includes the Sahara Desert in its southern region and an unpredictable climate along the Mediterranean (Holden, Stacy E.. The Politics of Food in Modern Morocco. United States: University Press of Florida, 2009.). Makhzen in Arabic literally means granary or storehouse; in Morocco makhzen also refers to the government.

Among other rationales used to explain its possession of the country, France aimed to fill its home breadbasket with wheat grown in Morocco. Between 1917 and 1931, the French government and French settlers took possession of more than 750,000 hectares (about two million acres) of land. By 1929, cereal production in Morocco reached three million acres. To justify its investments in its colony, France propped up the price of Moroccan wheat exported to France, meaning farming in Morocco was profitable, regardless of farm efficiency or yield. Not very wise, economically speaking.

Another purpose of France’s occupation was its intention to resurrect Ancient Rome’s success in using North Africa as a food pantry. At the beginning of the twentieth century, many Frenchmen considered themselves the rightful heirs of Ancient Rome’s greatness. They described their possession of what they considered a barely inhabited, uncivilized stretch of barren land thusly:

Following the prosperous days of the Roman era, Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco… vegetated, barely surviving, cultivating piracy… one by one, the former riches disappeared… all fell into ruin. Of the splendid golden age of Roman Mauretania only a sun-baked rocky desert remained where the beneficent river had become a devastating torrent, where agriculture had atrophied, where livestock subsisted or perished according to the vagaries of rainfall, and where the native sought to secure by force or ruse what his neighbor had produced instead of producing himself… Suddenly, a new breeze; and France… combatting as little as possible, arrived to conquer so that Roman civilization could be saved.

J. Germain and S. Faye, Le nouveau monde fran’ais-Maroc, A lgrie, Tunisie (Paris, 1924)

But Morocco’s fickle climate and global events wreaked havoc on France’s acquisition of wheat. In 1930, for example, Morocco suffered from a plague of locusts, drought, and a worldwide economic depression. Wheat exports to France were woefully insufficient, and France should have stopped all imports since indigenous Moroccans were starving. To the extent that they supplied aid to their protectorate at all, the French government preferentially directed it toward their own settlers (Ibid).

The following year, 1931, rain was abundant, and yields were so explosive that Moroccan exports flooded French markets, thereby depressing prices. French grain farmers were enraged by the impact oversupply had on prices; they called for quotas and tariffs on imports. In the mid-twentieth century, anti-imperial and home-rule movements were prevalent throughout Africa, the Middle East, and into Asia. By 1956 France finally concluded that the benefits of controlling Morocco were outweighed by the costs of suppressing nationalist fervor and they restored the Alaouite family to power.

Though French rule has been gone from Morocco for nearly seven decades, France’s imprint on Morocco remains. French is the second language of Morocco and is taught in many local schools. French baguettes can be found in Moroccan cities, as can French-style pastries.

Globalization

With the official end of France’s rule, the Alaouite Monarchy of Morocco, now restored to full power, resumed its multi-century commitment to protecting its citizenry and assuring the availability of reasonably priced bread. High prices for bread, compounded by corrupt governments, was one of the main contributors to the Arab Spring uprisings across the Middle East and North Africa in 2010. There were political protests in Morocco at the height of the uprisings of the 2000-teens, yet Morocco’s monarchy managed the crisis better than its neighbors.

As Dr. Katharina Graf’s research has made clear, bread remains a centerpiece of the Moroccan diet. But as prices of imported wheat increase and climate change affect crop yield, an age-old question remains paramount: how does the Makhzen keep the makhzens full? One way the government is keeping the price of wheat within reach, according to Graf, is by supplanting Morocco’s traditional, home-grown hard wheat with soft wheat. Soft wheat is inexpensive, plentiful, readily imported, and generally refined and sold as white flour. It is used to make white bread.

But, according to Graf, many Moroccans find soft wheat inferior in flavor, appearance, and quality. They prefer, if they can afford it, local hard wheat, which is often milled whole and is golden in color both as a grain and in its milled form, flour. They consider hard wheat healthier, too.

The French introduced soft wheat to Morocco. For it to grow well, soft wheat requires irrigation, high-yielding seed varieties, and plenty of fertilizers and pesticides. Even with all those inputs, Morocco still cannot compete with the farms and fertile soils of France, Argentina, Canada, Ukraine, and Poland, from whom it imports massive quantities. Imports, in fact, have increased steadily year over year. In the 1960s, with the exception of two years, Morocco imported under half a million tons of wheat per year. Last year they imported 6.5 million tons.

It is a delicate balance for the Makhzens. Government regulators must apply tariffs to grain imports in order to protect domestic farmers, while at the same time keeping the price of grain and flour low for its increasing population of urban poor. The government manages by subsidizing the cost of soft wheat. They allow the price of indigenous hard wheat to fluctuate at free-market values, which in general, costs more.

Among poor Moroccans who have moved to Morocco’s cities, making bread at home is simply too expensive. For recent city dwellers struggling to pay rent and utilities, purchasing grain, or even flour in bulk, is prohibitive. In contrast, neighborhood bakers can purchase supplies in large quantities, especially if they make bread with subsidized soft wheat. They can easily sell bread at prices lower than a mother at home can make it herself. Purchasing bread from a baker or corner store is the only rational decision. According to Graf, eating subsidized bread is one more source of depression for Morocco’s urban poor.

Dr. Graf’s study of the importance of bread to Moroccans is fascinating reading in its own right, but here is a very brief summary. Traditionally, in rural Morocco, women go to open markets to purchase whole grain. They rub grains together, test them between their teeth, ask whether the crop has been irrigated, and in which region it was grown. Terroir is important. They take home whole grain, clean it themselves, bring it to a local miller, and bake with it. But since local grain can be expensive, even in rural Morocco people opt for subsidized soft wheat to save money.

They rub grains together, test them between their teeth, ask whether the crop has been irrigated, and in which region it was grown.

Climate Uncertainty and Morocco’s Wheat Production

Morocco’s climate is typical of much of the Mediterranean region, North Africa, and the Middle East in that it is notoriously elastic: long periods of drought are often and unpredictably interspersed with years of plentiful rainfall. In the Quran (Quran, 12:47–49), as in the Hebrew Bible (Genesis 41), Joseph’s rise to a position of power was related to these very patterns. By interpreting Pharaoh’s dream correctly (The Quran refers to Egypt’s leader as King rather than Pharaoh), Joseph was able to help the country store grain during seven years of bounty that became essential to life during the seven years of famine that followed.

Joseph was the first, and probably last, person to make such an accurate prediction. Regardless of whether you take Joseph’s story as literal or more simply as a lesson from the Bible and Quran, plentiful rainfall interrupted by years of painful drought are inevitable in this region. Modern day predictors, using sophisticated computer models, are suggesting that climate change, already well under way, will bring extended and more frequent periods of drought to Morocco. When it rains, precipitation is more intense. The impact of deep erosion as well as flooding during recent rainy seasons were evident as I traveled throughout the countryside.

As one university Dean explained to me during my visit, climate change is a significant driver for internal migration from rural farms to burgeoning cities. Diminished rainfall in agricultural regions means that only smaller herds of grazing goats and sheep can find enough food. The quantity of goat and sheep dung is therefore smaller, so yields of basic crops are also declining due to lack of natural fertilizers. Former farmers are moving with their families to cities in search of work.

Modern Bread in Morocco

At its closest geographical point, Morocco is just under nine miles from Europe, across the Strait of Gibraltar. Ferries can get you from Europe to Morocco in less than ninety minutes and a trip costs less than $40 USD. In 2019, before COVID kept everyone at home, nine times as many Europeans visited Morocco as came from any other part of the world.

And since 2000, Morocco has enjoyed a free trade agreement with the European Union (EU): In 2019, 64% of Morocco’s exports went to the EU and 51% of its imports came across the Mediterranean (European Commission).

Morocco also has a well-educated and successful middle class, and more than three million Moroccans live in Europe. A lot of people go back and forth. In order to see what influence Europe is currently having on Moroccan foodways, I made a trip to a modern, urban grocery store. I find markets—both traditional open-air markets and modern grocery stores with coolers and fluorescent lighting—to be excellent museums of culture and I make it a point to visit a variety of them whenever I travel.

Outside the old city of Fez I walked all of the aisles of Carrefour, a French-owned wholesaler and retailer. Carrefour is the kind of store where you can purchase anything from a side-by-side refrigerator to imported kiwis. The bread aisle carried the kinds of breads you’d expect working professionals to purchase, including packaged baguettes and pre-sliced white sandwich bread. Industrial bread has reached Fez, Morocco.

As I traveled around Morocco lamenting a creeping universalization of Morocco’s historic bread culture, I came to a point of introspection that often overtakes me when I travel: Who am I to wish that Morocco’s bread culture could be frozen in time?

Happily, the age of great bread is not yet over in Morocco. Bakers across the country still fire up bundles of wood in khubz furans every morning. For a small fee, a baker will bake your bread, or if you do not have the time, bread recently pulled from a communal oven can be purchased at very low prices on virtually every city block.

For a visitor to the country, Morocco’s rich variety of traditional breads can still be sampled. For a traveler hunting for regional specialties, the search is akin to a bird-watching expedition: you have to search for the right abodes. A guide is helpful, but not necessary–just ask anyone in Morocco about bread and they will happily talk to you about their relationship with bread and breadmaking, too.

Even if you do not have the chance to eat bread in North Africa, one of the great joys of home baking is that you can get a bit of insight into other cultures by trying foods out in your own kitchen.

Soon, Maurizio and I will publish a recipe for m’lawi. It’s a recipe that I hope will give you a nice taste of Morocco’s wonderful breads.