When my book Sourdough Culture: The History of Bakers from Ancient to Modern Times was first published, my most exciting interview was with Ira Flatow on Science Friday for an episode called A Sourdough Starter from Starter to Slice. A couple of days before the interview was recorded, I received a call from one of the show’s producers. We discussed the show’s very specific requirements for audio quality, and then she asked me a question that was direct from Flatow: “Was the story of Passover really a story about sourdough?”

Flatow did not ask me this same question on the air, but it stuck with me. According to the Pew Research Center, nearly three-fourths of Jewish-Americans participate in a Passover seder, making it far and away the most widely practiced Jewish tradition in the United States. A Passover seder can be a long ordeal, especially if you are young and hungry. It is filled with prayers, songs, readings, laughter, questions, and arguments, with many of these activities occurring concurrently. The Passover holiday is also rich with history, and while many people, Jewish and not-Jewish, know that unleavened bread plays a key part of it, could there perhaps be a story of sourdough buried in the roots of the tradition too?

What Is the Passover Holiday?

Here is a highly abbreviated explanation of the holiday of Passover. Please note I am not a scholar of religion; consider this a rough summary for those of you who aren’t familiar with Passover. According to the Hebrew Bible (sometimes referred to as the Old Testament by Christians), thousands of years ago, the Jews were held as slaves by Egypt’s pharaoh. The Jews turned to their God, asking for freedom from bondage. The Hebrew God tested the determination of Pharaoh to retain his slaves by sending ten plagues. After the first nine—water contaminated by blood, frogs, lice, flies, disease on the livestock, hail, locusts, and darkness—Pharaoh still had not budged. And then came the tenth plague: God called for the slaying of the first born in every Egyptian household.

Jewish homes were “passed over” and their children spared if the Jews followed God’s instructions in Exodus 12. Each Jewish household was directed to ceremonially slaughter a lamb and used some of the blood of the lamb to mark their homes. Then, the households ate the lamb with unleavened bread, among other things, according to further instructions from God. Following the tenth plague, the Jewish slaves of Egypt fled.

The chase was on. Led by Moses, the Jews of Egypt rushed from bondage toward the Red Sea where their God performed yet another miracle. Most of us have a baroque vision of Moses, hands raised toward the heavens, parting the waters. The Jews are about to make a miraculous escape. The Egyptians are not going to fare as well.

After crossing through the parted waters, the Jews of Egypt began their journey. They wandered through the desert for 40 years. This joke is part of my seder tradition:

“Why did the Jews take 40 years to find their way to the Promised Land?”

“Because Moses refused to ask for directions.” (Ba Dum Tss.)

Leavened Bread is Forbidden During Passover

In the Book of Exodus, following God’s promise to protect the first born children in Jewish households, God commands the Jewish people to remember the day for all time (Exodus 12: 14). The line after that prohibits the consumption of leavened bread for seven days:

Seven days you shall eat unleavened bread; on the very first day you shall remove leaven from your houses, for whoever eats leavened bread from the first day to the seventh day, that person shall be cut off from Israel. (Exodus 12: 15)

In place of their usual bread, Jews were instructed to eat only unleavened bread: matzah. Eating matzah is a central part of the Passover seder, and for one week (eight days in some traditions), observant Jews eschew leavened bread and eat matzah in its stead. The common explanation, appreciated by even the youngest children, is that the Israelites had no time for bread to rise. With marauding Egyptians in hot pursuit, flour and water were hastily thrown together, fires were lit, and the pasty dough was cooked. In Deuteronomy (16:3), matzah was called the bread of distress.

But as Ira Flatow wondered: What became of their sourdough starters?

The Bread of Ancient Egypt

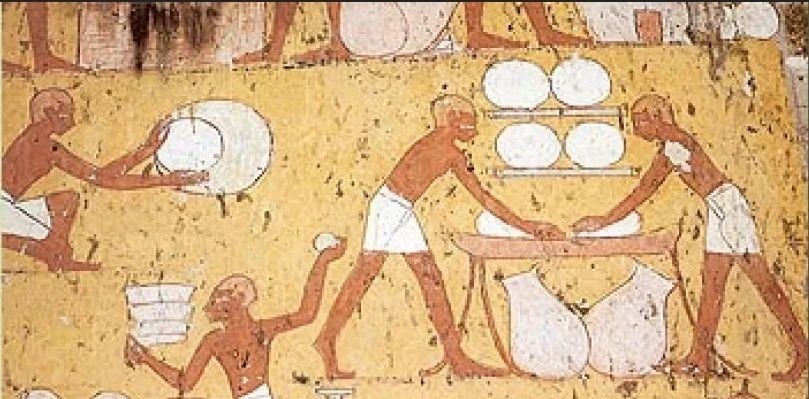

Using the Instagram of the day—and proving the point that without an image, sourdough bread doesn’t really exist—Ancient Egyptians engraved likenesses of their clearly leavened loaves into stone.

Archaeologists have confirmed that the ability to leaven bread was available. Ancient Egyptians drank beer, and the inside of beer vats, desiccated in the desert heat, contain the DNA of yeast species used at the time. Even if Egyptian bakers were not keeping sourdough starters to reuse for daily bakes, they surely could have ladled some foam from these beer vats and used it for leavening.

Yet, we cannot be certain whether Egyptian bakers used sourdough. First, they did not leave written recipes, so trying to ascertain how a loaf was made can only be done by trying to recreate what we see in hieroglyphics. And second, the high heat needed to bake dough destroys the cells of any yeast that were living before they went into the oven. So even though there are some Egyptian loaves that were so dried out by desert air they have survived to this day, we cannot tell for sure if they were leavened with sourdough.

Nonetheless, archaeologists and hobbyists have done their best to recreate ancient Egyptian sourdough loaves. In the early 1990s, renowned Egyptologist Dr. Mark Lehner partnered with microbiologist Ed Wood (who some of you may know from his seminal book, World Sourdoughs From Antiquity). Together, they constructed a replica of an ancient Egyptian bakery, and Wood captured native Egyptian yeast and bacteria to use as sourdough starter. They made sourdough bread that looked and may have tasted like what was used to feed the laborers who built the Giza pyramids (2575-2134 BCE). For a great visual of the experiment, look here.

Later, in In the1990s and early 2000s, Delwyn Samuel published several articles describing how she made bread using only tools and instruments available at the time of the pharaohs. More recently, Xbox inventor Seamus Blackley scraped some yeast cells from an Egyptian clay pot that was 4,500 years old. He made a sourdough starter with the yeast, and then made sourdough bread that might be the most authentic tasting of the bunch. Blackley insists the loaf was delicious. If his tasting notes are reliable, escaping Jewish slaves wandering through the deserts of the Middle East would have longed for the taste of fresh Egyptian sourdough bread à la Blackley’s experiment.

For Passover, What Counts as Leavening?

To commemorate the hardship of slavery and the painstaking journey through the desert, Jews prepare for Passover by cleansing their homes of bread. Out go breads, cookies, pretzels, pasta, crackers, etc. The basic rule is that anything made from these five grains should be expunged: wheat, barley, oats, rye, and spelt. Interpreting God’s command to forego leaven runs like this. If any one of the five grains sits in water for more than 18 minutes, yeast begins to grow. (One explanation has it that the Sages of the Talmud are responsible for determining that 18 minutes was the amount of time needed for fermentation to begin.) Once fermentation starts, the food in question is no longer kosher for Passover. To be kosher for Passover, then, matzah must be made from flour and water in under 18 minutes, start to finish.

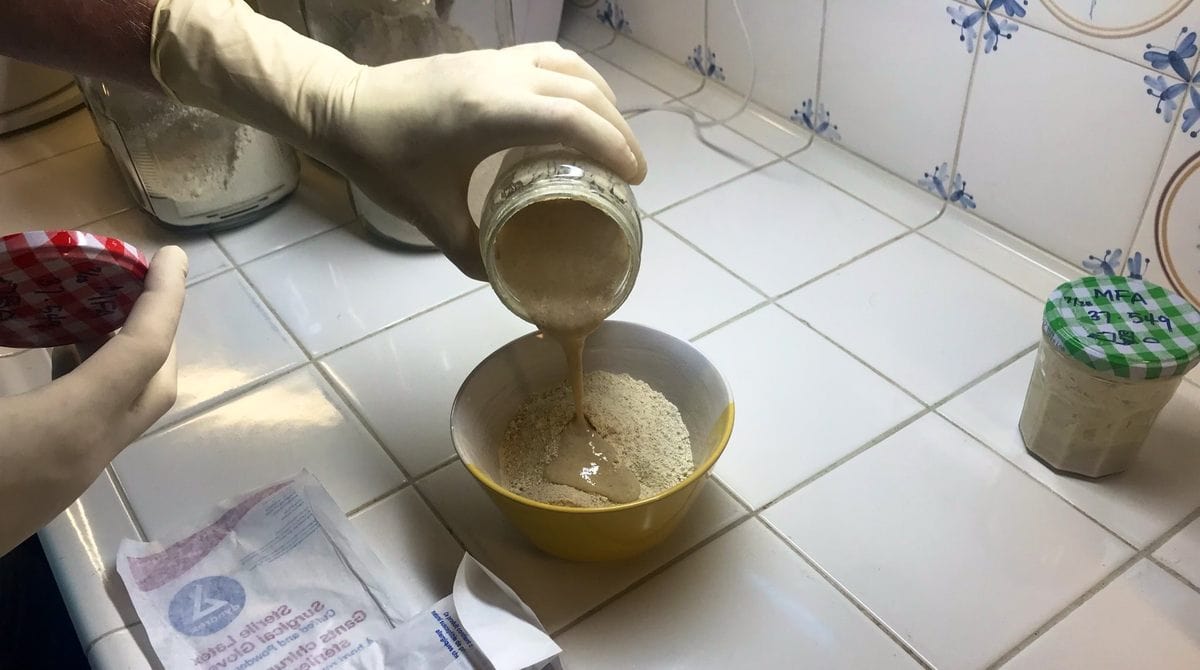

Is a Sourdough Starter Kosher?

What about your sourdough starter? In short, yes. Sourdough starter is kosher. Teeming with yeast, however, it is is not kosher for Passover. For Jews reluctant to toss their starters, there is a workaround. You can “sell” your starter to a non-Jew for the duration of Passover and buy it back at the end of the holiday. Cook it, sell it, or throw it away. One way or another, your sourdough starter has to go.

The Meaning of Sourdough for Passover

Before the return of sourdough to American tables, say, 50 years ago, the question of sourdough and Passover had mostly been relegated to discussions by Rabbis and Jewish theologians. But here we are. Archaeologists tell us that Egyptians were making sourdough bread. The Bible says that upon leaving Egypt, Jews were instructed to recall the Exodus in perpetuity and to do so by forswearing bread. For a week, no sourdough bread, only unleavened matzah, the bread of affliction. But why?

Rabbi Deborah Prinz believes that the prohibition on sourdough starters was first and foremost a recognition of Egyptian expertise with sourdough. Egyptians were so good at fermentation, they fed bread and beer to 10,000 pyramid-builders at Giza. Further examining the historical evidence, Rabbi Prinz notes that the Levites, Israel’s priestly class, were the likely editors or authors of the books of Exodus and Leviticus. As protectors of Judaism, the Levites wanted to repudiate Egyptian influence on Jewish culture. They drew a distinct line in the desert sand: sourdough bread would be prohibited during the festival recollection of bondage, Passover.

Prinz’s proposition goes a step further. She rejects the premise that the Jews did not have time to let their dough rise while fleeing from the Egyptians. When mixed together and left to sit, flour and water will do more than just autolyze. In the heat of an Egyptian desert, it is going to start fermenting pretty quickly. The consumption of leavened bread is proscribed by the book of Exodus precisely to get people to toss out their sourdough: throw away all things that Egyptians did well. For a week, survive on unleavened breads, the matzah eaten by Priests and Levites. In the Holy Temple/Tabernacle of the ancient Jews, only unleavened breads were eaten, not those leavened loaves eaten by polytheistic Egyptians. Eat like a priest, not an Egyptian. It is going to take a week for a new sourdough culture to mature anyway.

Bible scholar William Popp has suggested that starting a new sourdough culture was a catharsis, a fresh start following centuries of slavery. “In the month of the New Grain, the Hebrews cast off centuries of oppression and assumed a holier, more ascetic status for their desert wanderings and subsequent national life.” (Anchor Bible Commentary to Exodus 1-18, p. 434).

Rabbi Lawrence Troster provides a modern interpretation of Popp’s analysis of holiness. Troster says that the thorough cleansing of our homes in springtime—the difficult task of removing even the crumbs of leaven hiding in the corners of our cupboards and the sourdough starters we have lived with for the past year—is designed to help us cleanse our spirits and reconnect with the rebirth of spring. It is time to shake off the burdens of bondage and create new starters.

Nine months into baking bread with his first sourdough starter, Rob Eshman faced his first Passover. “I ask that age-old question of an inscrutable God: Why?” writes Eshman in a 2017 article published in Jewish Journal. He offers three rationales.

First, sourdough bread making is labor-intensive. Passover is a way to turn our focus away from what we create and toward the first greens of God’s creation (not totally convincing, in my opinion, considering how much time is spent in the kitchen to prepare a seder meal).

Second, baking takes time, especially sourdough baking. Passover teaches us to live lightly, move quickly, and not be so tied up in knots thinking about saving our starter for tomorrow. Live in the moment, not the anticipation of tomorrow. Third, he reiterates Troster’s premise: it is time to start afresh.

Eshman made one additional observation that really hit home for me. “Until you actually make bread like your Israelite ancestors did, it’s hard to understand what lesson there is in prohibiting leavening.”

If you had to relinquish your sourdough starter for a week, or throw it away, what would you be thinking about?

To those that celebrate, Happy Passover.